Image: Ellen Gallagher, ‘Abu Simbel’

Two types of invitations seem to be floating into my inbox with increasing frequency, for talks and exhibitions on the Anthropocene and Afrofuturism respectively. The latter was the subject of Union Black/The British Library’s Space Children, Kosmica’s ‘Astroculture’ event at the Arts Catalyst, Tate Modern’s Afrofuturism’s Others and the Photographers Gallery’s Afronauts by Cristina de Middel. Afrofuturism even cropped up at UCL’s interdisciplinary Cosmologies symposium as an example of a ‘dissident cosmology’. As discussed in a previous post, much Anthropocene themed art uses geology as a starting point to re-think the human as a geologic agent. Afrofuturism, by contrast, (re)imagines African (especially African diaspora) pasts and futures through flamboyant scifi and spiritual aesthetics. Canonical examples include the music Sun Ra, Parliament Funkadelic, Nona Hendryx and Drexciya, the writing of Octavia Butler, Nalo Hopkinson and Samuel Delaney, and the art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Rammellzee and Renée Cox.

Despite their apparently different aesthetics and citational practices, there seems to be a dialogue between the two genres that goes beyond mere navigation between far pasts and futures. Looking at the common reference of the cosmic and its role as both origin and culturally marked space, the first part of the dialogue could be summed up as: who (or what) makes the future? Is it geologic or cosmic forces? Is it humans? And, if it is humans, what sorts of humans? Poor, rich, Black, White, male, female, straight, gay? Scientists or politicians? None of these assumed polarities? Here, Afrofuturism does not provide an answer, but possibilities. First of all, it confronts us with our expectations of ‘race’. As Lisa Yaszek writes:

‘[f]rom the ongoing war on terror to Hurricane Katrina, it seems that we are trapped in an historical moment when we can think about the future only in terms of disaster — and that disaster is almost always associated with the racial other.’

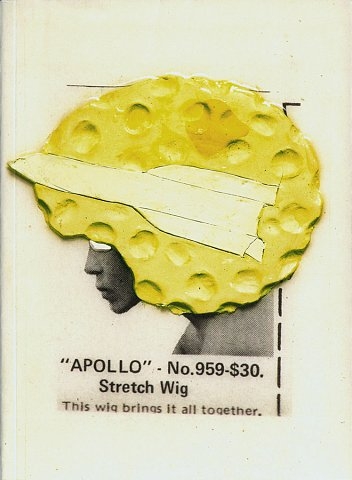

Or, in Anthropocene terms: rich White people cause disaster, poor Black people are its victims. While people in the ‘global North’ indeed have a disproportional share in furthering climate change, such framings have led to warnings about a potential resurgence of ‘old… tropes of racial capability’, as issued, for instance, by Yasmin Gunaratnam and Nigel Clark. Rather than trying to silence the debate, they call for an exploration of ‘the ‘primitivism’ inscribed in our bodies, psyches and cultures’. It is such inscriptions of primitivism that Afrofuturism plays with, not only regarding African cultures, but all cultures. The play with Egyptian origins and aesthetics by Sun Ra and Ellen Gallagher exemplifies the historical struggle over cultural legacies and the construction of ‘high culture’ and primitivism.

Image: Still from Sun Ra’s ‘Space is the Place’ film

Although often humorous in nature, the Egyptian imagery points to questions about whom this construction continues to serve and about how it can be rewritten. The origin of Afrofuturism in the ‘global North’ further contributes to the cultural challenge. As South African digital artist Tegan Bristow phrases it: ‘[u]nlike what it suggests, Afrofuturism has nothing to do with Africa, and everything to do with cyberculture in the West’. Seen from this angle, the origin as well as the necessity of the term ‘Afrofuturism’ underscore the fact that the ‘African’ and African diaspora have routinely been excluded from ‘modern’ and techno-futurist visions and set apart from the ‘mainstream’ (there is an excellent talk by Madhu Dubey on this topic here). Here I am reminded of Octavia Butler’s response (around 7 minutes in) to a White science fiction author who argued that there is no necessity for Black people to appear in their novels, because statements about the Other can be made through aliens. In an inversion of stereotypes, some Afrofuturist commentators highlight the ‘primitivism’ of a science that seeks to classify the ‘primitive’, pointing to mainstream science’s contribution to racism and genocide at various moments in history (examples can be found in Alondra Nelson’s book Body and Soul and in this catalogue on Ellen Gallagher).

Dipesh Chakrabarty on ‘History on an expanded canvas: The Anthropocene’s invitation’ at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin.

Similarly, the Anthropocene discourse practices inversion as a strategy to unsettle visions of modernity and to search for new models of human agency. Although scientists have not been able to agree on a potential beginning for the proposed new era, the industrial revolution and its heavy reliance on fossil fuel consumption remains a strong contender. When it comes to our (primitive?) dependency on these energy sources, scientists and social scientists have started to re-examine preconceived notions of cause and effect: are fossil fuels shaping human society and not the other way round? (Yusoff, Moore, Roddier) What kind of agency do humans have to affect social and environmental change? Are new strategies in order? Again, such debates, draw on arguments about our current interpretation of ‘modernity’: what kind of ‘rationality’ should modernity (and ‘modern science’) follow? Do ‘subaltern modernities’ reflect a more accurate vision of modernity? Can humans see themselves as a ‘species’?

AFROGALACTICA: A short history of the future from Kapwani Kiwanga on Vimeo.

Turning back to Afrofuturism, sociologist and writer Alondra Nelson suggests that it represents more than a critique of modernity – it is about ‘aspirations for modernity’. Rather than dwelling on the negative, it ‘enables thought about a lineage of work that propels future other work’ that co-shapes the future. It is occupied with the ‘living future’ (to use Barbara Adam & Chris Groves’s term), the potential for different futures inherent in the present. One trajectory that Afrofuturism pursues is a reshuffling of difference. According to Nelson, popular interest in genetics and the potential discovery of links to previously unknown, geographically distributed ancestors, is, despite its focus on physical difference, already unsettling and reshaping identities, both at the micro and macrolevel (audio here).

Ellen Gallagher, ‘IGBT’

In this context, an important question was asked at the Tate Modern, in conjunction with artist Ellen Gallagher’s AxMe exhibition: who can be an Afrofuturist? Entitled, ‘Afrofuturism’s Others’, the organisers, panellists and audience explored whether Afrofuturists could be anything other than African American. In discussing the work of Kara Walker, Lili Reynaud Dewar, Larissa Sansour, Mehreen Murtaza, Jean Genet, Ellen Gallagher and others, the case was made that Afrofuturism contemplates an absence of racial and geographical boundaries. In particular, the speakers considered the problematic, but also potentially productive relation between racialization, as turning certain humans into part of the ‘productive landscape’, and ‘species being’, which is also a materialisation, but one that can go either way in terms of dealing with difference (the work of Sylvia Wynter was mentioned). The works discussed included examples of deliberate and accidental solidarities: art and music that referenced ‘Afrofuturists’ or became interpreted as ‘Afrofuturist’ on the basis of aesthetic (mis)interpretation (curator and co-organiser Zoe Whitley described a humorous encounter where she misread a painted black figure as signifying ‘Black’).

Image: Mehreen Murtaza, ‘Divine Invasion’

Here, a second trajectory seems to emerge that asks not only ‘what is ‘afro’, but ‘what could the ‘afro’ be and do?’ This takes us to the ‘Africa is (not) a country’ awareness campaign (example blog here). As many African Americans point out, the slavery system often deprived them of more detailed knowledge about their ancestry other than ‘African’. At the same time, the ‘African’ has acquired meaning for the community and is increasingly also tied to particular political imaginations. During my visit to Detroit, I found that African American activists were talking about promoting an ‘African model’ of community and of reshaped institutions against the ‘White corporate’ model. At a film screening of Branwen Okpako’s ‘The Education of Auma Obama’ at the Ritzy cinema in Brixton, African visions of trajectories for modernity again came up, prompted by Auma Obama’s discussion (in the film) with Kenyan students about the kind of lifestyles they are hoping to pursue. Obama asked her students to consider what premise notions of ‘progress’ and ‘development’ are based on. Development of/towards what? Industrial farming, increased levels of consumption, loss of community? Why could certain ‘African’ models of living not hold the key to human development? Seen through the lens of Afrofuturism, one could say that if the ‘afro’ can be shaped into something coherent, this move does not necessarily imply a wish to do away with nuances and differences. Instead, it could be read as a productively employed and reframed cliché that critiques a privileged socio-economic model. Its future trajectory could indeed transcend its current context. The question here might be phrased as: can established categories be rejected by getting contemporary ‘non-Others’ to adopt the model that is normally deemed ‘other’?

Image: from Cristina de Middel, ‘Afronauts’

The corresponding Anthropocene question might be put as ‘what could the ‘geo’’ be and do? The logic seems to be that if the human can be a geologic force, how else is human life geophysical – and how could this perspective lead to a more constructive reframing of politics and the social? Especially since, thanks to climate change, the stability of the ‘meteorological White middle class’ (as a recent German TV satire described Europe) might become seriously unsettled… So far, quite a few proposals have tried to put human politics into perspective: we might do all these politics for economic power – but at the end of the day, when oil is used up, the water is polluted and the temperature is up, our role as a geologic force might be unsatisfactorily short. Shouldn’t humans work more in cooperation in the face of geophysical processes that will carry on without consideration of human needs? It is interesting to note that some of the most interesting proposals have again been excluded from the ‘mainstream’ and have been consigned to the area of ‘post-colonial ecologies’. I am thinking here especially of French-Caribbean discussions of geopoetics (Maximin, Glissant, Condé etc). Conversely, scholars from post-colonial studies, such as DeLoughrey and Handley, have criticised that ‘Westerners’ are in search of ‘Other’ models to bring a much needed conceptual injection. This debate raises questions about the conditions under which dialogue should take place.

Ellen Gallagher, Detail from ‘Afrylic’

For me, visiting Ellen Gallagher’s exhibition at the Tate Modern (on view until 1 September 2013) synthesized the dialogue between Anthropocene and Afrofuturism even more intensely (enter the ‘Afrocene’?). Walking through the different rooms, I was struck by what I experienced as a ‘hypermaterialisation’ of layers and layers of material and meaning. Many art critics have commented on her relationship with the material, for example, Gallagher’s wish to ‘maintain the ‘vulnerability’ of her materials and their forms’ (Shiff), her use of African American wigs as a conduit to the supernatural (de Zegher), but few manage to capture the intensity of an entire retrospective. Robin Kelly comes the closest: he describes his encounter with Ellen Gallagher’s work as ‘confounding’.

‘To confound is not simply to confuse, but to surprise or perplex by challenging received wisdom. It also means to mix up or fail to discern differences between things.’

I don’t think any term could be more accurate. To me, Gallagher’s shifts between meanings of medicine and wig adverts, ‘high’ and ‘low’ art/culture references, ‘nature’ (I especially loved the title ‘Double Natural’) and ‘blackness’, marine creatures, minstrel imagery, ambiguous organic shapes and political pamphlets rendered tangible the multiple ways in which people are being materialised and enlisted as part of social and economic production: overworked and stuck in a job you cannot get out of? Pop a pill. More ‘organic’ than society’s ideal? Neighbours throwing bombs into your house? Buy a wig. Keep calm and carry on. The sheer ridiculousness of the enterprise as well as our complicity in it becomes apparent. Does Gallagher suggest any way out? It seemed to me that she was perhaps implying that the path towards more productive forms of materialisation may lie not only in realising the ridiculousness, but to start from it. Geology and politics? Ridiculous! Africans in space? Ridiculous! A more equal global society? Ridiculous! Or is it?

Hi Angela,

this is an excellent post, and it’s gonna take me a while to follow up on all these threads! i have an extremely latent interest in combining afrofuturism/anthropocene work so it’s good to see that someone is thinking way ahead of me! There are a couple more works that i’ve been inspired by and that might prove useful to you:

Britt M. Rusert’s article “the question of race in the age of ecology” in Polygraph 22 engages both afrofuturism and ecology/climate concerns

Clare Colebrook has an article on race and extinction in the Deleuze and Race collection that recently came out.

Overall, I find most of the emerging “cli-fi” works to be quite bad on race. although I’ve not read a ton of it, the stuff I have encountered too often unites humanity – the anthropocene is either the death of race (in human extinction) or an overcoming of it (in a postapocalyptic multiculturalist universe). I’d be interested to hear if you’ve read any of this stuff that’s better, or any particularly cogent analyses.

The work that I like the most is Delany’s recent massive novel Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders. Climate change is barely really mentioned in the book (if i remember correctly) and it hardly shares the aesthetics of afrofuturism or even science fiction…but it succeeds in articulating the temporality of future ecological and social change (we’re probably not quite at the geologic level here…). as Delany put it many decades earlier, the goal is “to write about worlds where being black mattered in different ways from the ways it matters now” and consequently he deftly evades the planetary humanism of someone like Gilroy (cf that Gunaratnam & Clark article) in favor of a creative and affirmative take on race, sex, and sexuality. Delany is as I’m sure you know also a master of theory, and given that TTVNS is primarily a mediation on Spinoza, there are many possibilities to read his work with the Spinozist feminists like Liz Grosz (most recently on geopower), or the earlier work of someone like Genevieve Lloyd. Hopefully someone else will do make some of these connections properly, as I just don’t have the time at the moment!

Some folks really like Octavia Butler’s quasi-utopian later works (the parables) on climate change. I’m less invested in these works, I think.

one thing that’s always troubled me is that afrofuturism as genre sometimes leaves behind the full gamut of racial futures. for this reason, stuff like the recent “Walking the Clouds” – a collection of indigenous science fiction and futurisms (w/many essays concerning climate change) is really exciting.

ok, well sorry to ramble on, but this is exciting stuff!

kai

Hi Kai!

Thanks for your comment and the reading suggestions. My current research isn’t actually on Afrofuturism – I originally wrote this post as a review of Ellen Gallagher’s exhibition, because I felt that the UK reviews about her work had given it a poor reading. However, I do think that both climate change and Anthropocene discourses (like many others) are rather White male dominated & appear to omit many relevant perspectives. I am currently trying to help introduce some of these marginalised theorisations.

There are some other scifi collections which tackle race and climate (e.g. ‘So long been dreaming: Post-colonial visions of the future), and, even better, there are a few in production (e.g. ‘Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism & Beyond’). At Exeter, they have a project called ‘The novel in a time of climate change’, at Exeter that might also speak to this topic ( http://www.exeter.ac.uk/sustainability/newsandevents/archive/title_142975_en.html ). Also, I am finding projects such as the Kenyan short film Pumzi very exciting ( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IlR7l_B86Fc ). I didn’t know that Samuel Delany had a new novel out – great! I am very familiar with Octavia Butlers work, but I haven’t read it through the lens of climate change so far.

If I come across anything else (including events), will post it here.

Angela

Just stumbled across this….Really fascinating essay

Thank you!