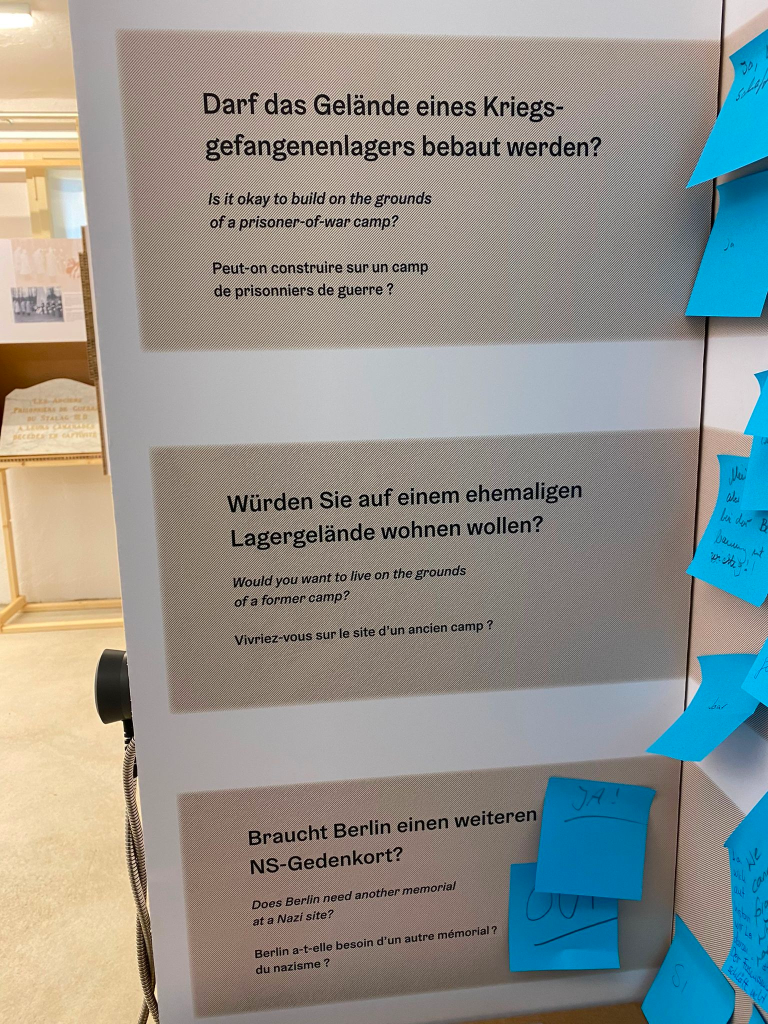

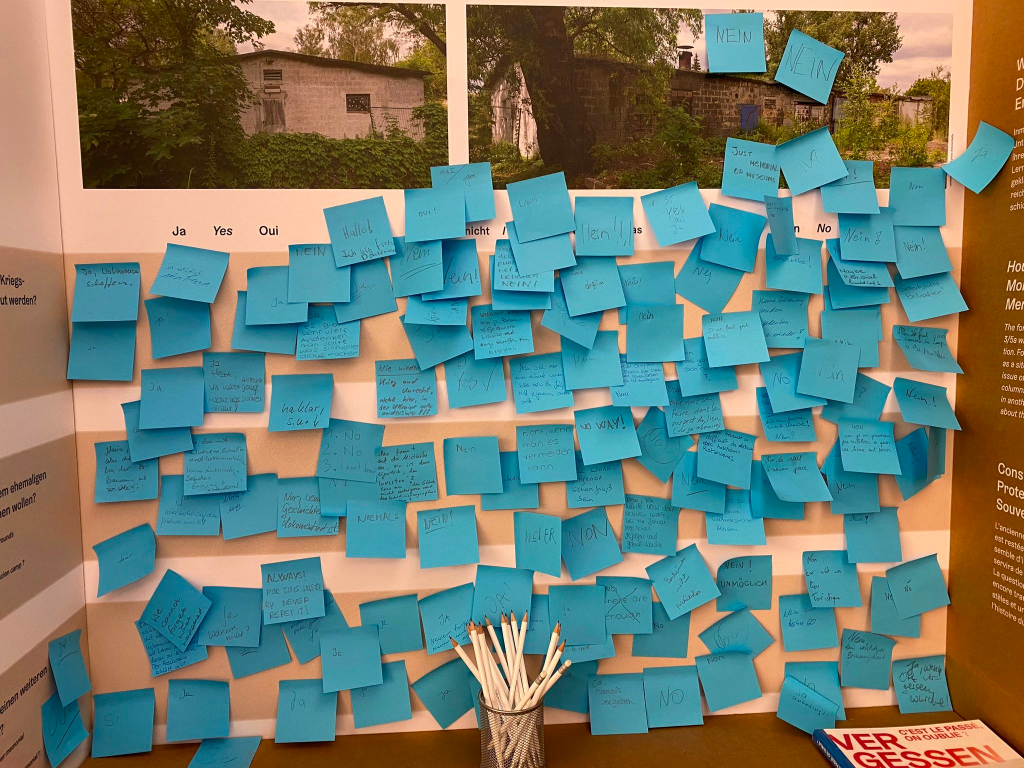

I’m on the Berlin study trip with my third year students again. Today was a free project day, so everyone could pursue their own interests. I ended up going to three exhibitions, although only two had been on my list. On the way to the Treptow Museum, I followed signs to a ‘Documentation Centre for National Socialist Forced Labour‘, taking a small detour. The centre turned out to be on the site of an actual labour camp, the exhibitions taking place in the former barracks. The camp had been modified and repurposed during GDR times as a vaccine research station, but it was pretty much preserved. As I found out, the site was under threat from housing developers, and one of the exhibits featured a public consultation.

The permanent collection displayed hundreds of photographs, index cards and items from the workers’ lives. I was particularly drawn to the many contrasting biographies in the middle part of the permanent exhibition. They made me think about the many different choices that people can and do make in extreme political circumstances. The connections of many established German companies to forced labour were also well documented. Amongst the archival material, I noticed a familiar place, the Otto Fuchs metal works where one of my uncles worked as a chemist until his early death from brain cancer (ironically, another uncle participated in a post-war film that criticised the collaboration of German industrialists with the Nazi regime – the story is narrated from the viewpoint of an industrial chemist at IG Farben). Many of the documents in the exhibition were produced by the workers themselves, such as photographs, diary entries, legal contestations, customised or sabotaged items. It worked really well to underscore the agency and humanity of the workers who were treated as subhuman by the Nazis. This theme was also continued in the next exhibition on the Berlin colonial exposition of 1896.

Treptow Museum had initially been on the list for my guided day, but I had managed to get the opening hours mixed up. Instead, we went to the excellent Trotz Allem/Despite Everything exhibition and to the the archive around anti-racist struggles in Berlin, both at Fhxb Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum (some great materials there to work through for the students!). The ‘Trotz Allem’ exhibition followed the lives of families that had migrated to Berlin during colonial times. It contested the view that migration into the city was just a recent phenomenon.

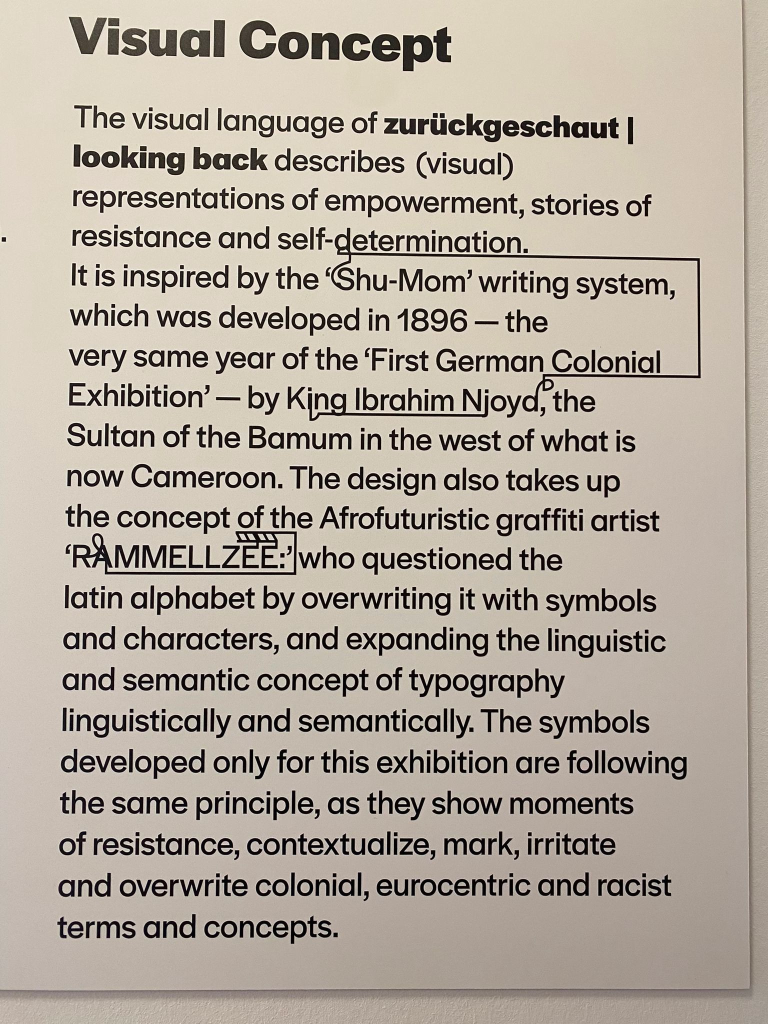

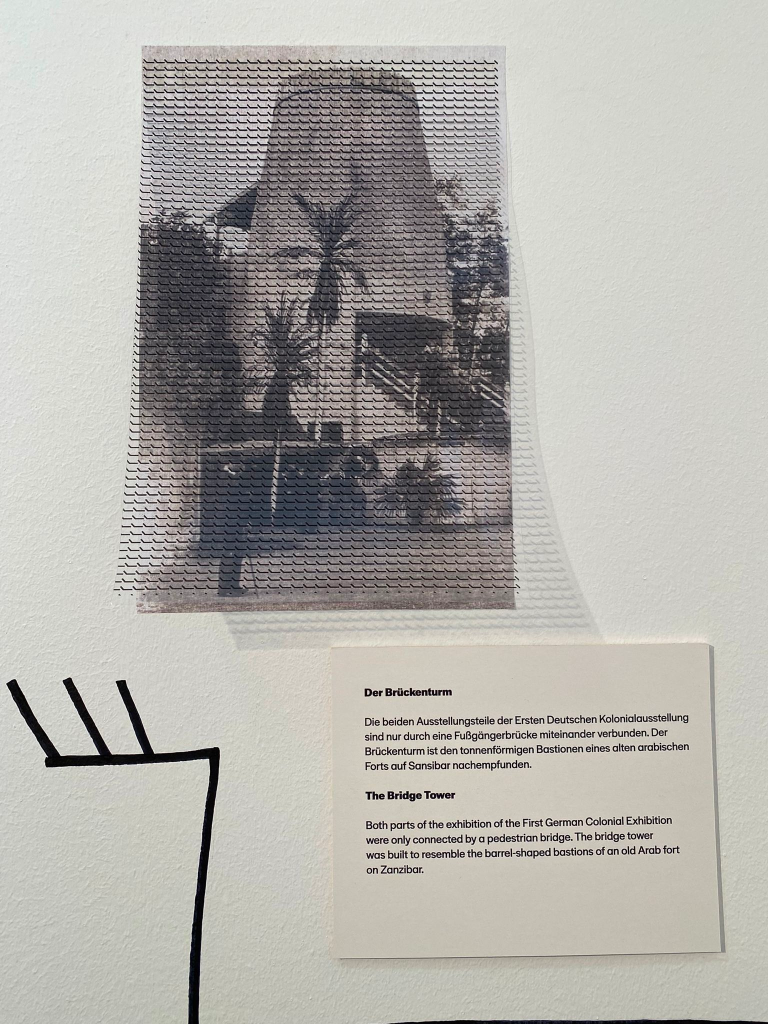

The Treptow exhibition, by contrast, looked at (mostly) temporary migration – for the purpose of participation in the colonial exhibition, as ‘exhibits’. ‘zurückgeschaut/looking back‘ was a collaboration between the museum and the civil society project ‘Dekoloniale Memory Culture in the City’. A previous version was put together with the Initative of Black People in Germany (ISD) and Berlin Postkolonial. The exhibtion is to be continually updated and expanded through new findings – hopefully we can go on a guided tour (contact Miriam Fisshaye at Zwedi for tours). As in the previous exhibits, the method was to bring people closer to the viewer by telling their life stories. These stories named people, showed their motivations for participation, their negotiations about the work conditions, and also sometimes their prior life in Berlin, where they were involved in apprenticeships or ran their own businesses. What was special about this exhibition: individualising people visually, e.g. by showing individual portraits, removed from their background context and coloured in to bring them closer/closer in time. Another means was by challenging and creating not only alternative language but also visual performance of language. Specifically, the performed neutrality of language (in this case written language) was being contested:

The Treptow exhibition statement also reminded me of the much cited method by artist Jean-Michel Basqiat: ‘I cross out words so you will see them more. The fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them.’ Although the exhibition designers used a similar method, I did not feel that the crossing out drew more attention to offensive language. To me, the over-written parts felt very natural, as if they should always come in this form. They made the text feel more like an orchestral score where the elaborated bits became a musical score, a silent soundtrack, with the overwritten parts becoming noise or pauses – like thinking pauses that should have occurred to prevent colonial crimes. But now the crimes and the words and pictures are there. Indeed, not only was this method used with writing, but also with photographs and other visuals:

I had to think back to the Fhxb exhibition poster and its typography, but also typographical experiments at the German queer feminist Missy Magazine with regard to race, gender and ability. Having studied some graphic design as part of my fashion studies (I have a BA and MA in Fashion), I know how much typography is being obsessed with by designers, and for good reasons. It makes political statements. When the students walked to the Reichstag building, explained the debate about the font above its entrance (‘Dem Deutschen Volke’/To the German People). Politicians could not decide whether to go for a ‘Gothic’ font, symbolising German tribal connections, or whether to pick a ‘Roman’ font, echoing the empires of antiquity. What kind of history did these politicians want to write?

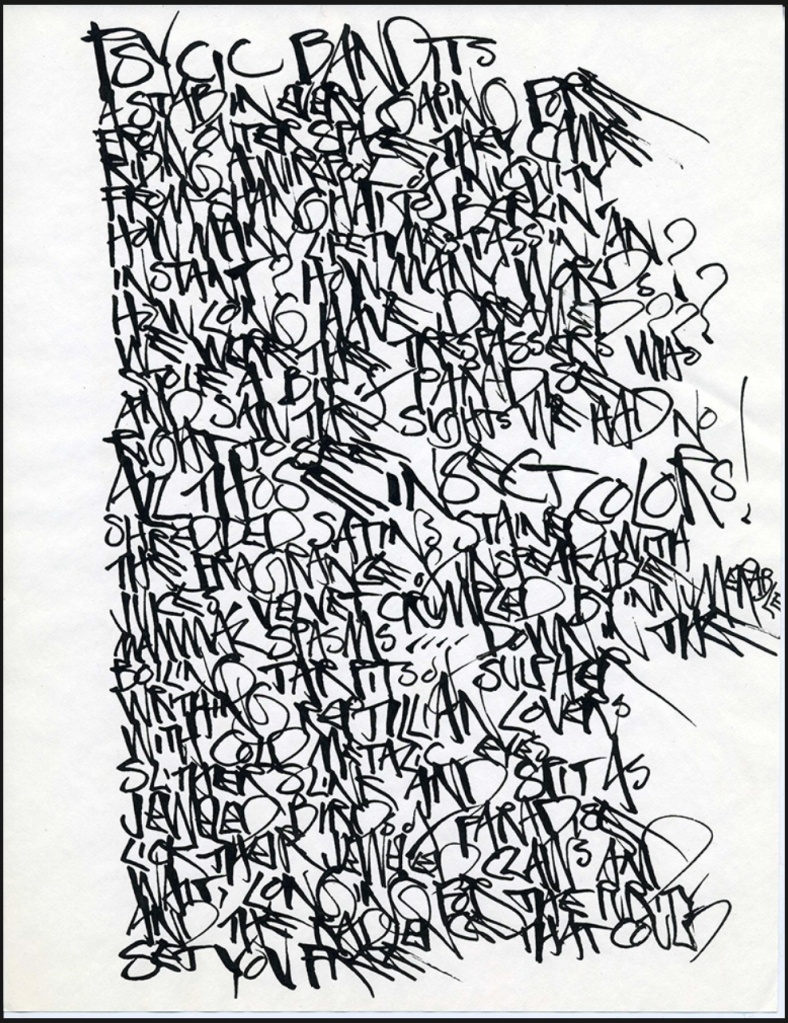

At Treptow Museum, the combination of ‘Shu-Mom‘ and Rammellzee suited the exhibition really well in terms of style and purpose. It also prepared be for my next exhibition visit, Malicious Mischief by the artist Martin Wong. Wong (1946-1999) was a gay Chinese-American painter and sculptor whose art worked with and against stereotypes around his multiple identities. The first thing I noticed was his writing style, which features prominently in his earlier work. Here is an example:

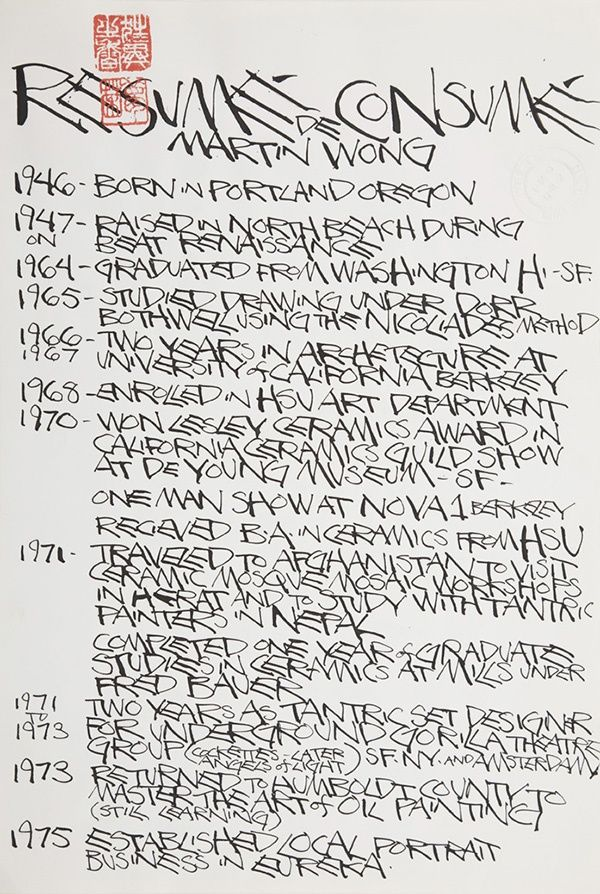

Wong clearly experimented with Chinese-American aesthetics, not just in his paintings but also in his written pieces. The fusion of graffiti and Chinese script is even clearer on his CV:

I like how the font initially appears messy and difficult to read, but is actually easy to decipher. Despite its apparent messiness, it is aesthetically coherent and even pleasant. The resonances it carries are both overt and subversive. I had to think of questions such as: How much does typography influence perception? What amount of detail does our mind need to complete or question an aesthetic of cultural stereotype? Where are graphic boundaries/overlaps between writing systems? How much does our writing reflect individual or group/dominant identity? (Such questions may have featured in the associated conference On the Languages of Martin Wong.)

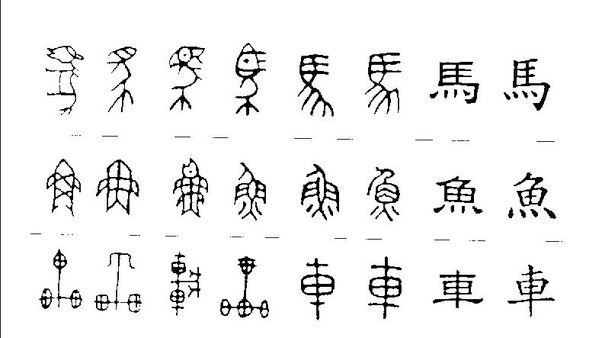

What both Wong’s typographic experiments and those of the ‘Trotz allem’ exhibition further made me think about is the aliveness of both spoken and written language. Even when transformations sometimes happen through violence, such as invasions, these seem to not only occur one-way. This has not prevented some people from trying to save ‘their’ language from ‘mutilation’, especially dismissing innovations that relate to new cultural influences (read: race, gender, ability…). However, looking at examples such as Chinese character development, more generally transformations in sounds, transcription or meaning, such arguments do not hold. I understand some of this desire, for example, I feel it when the German character “ß” is being progressively eliminated, or when I learn about the many languages and related world views (I need to write that ‘word views’ blog post that has been on my list for ages!) that are dying out right now. I think it depends what we feel attached to or nostalgic about and why. In my view, if we don’t ask about this ‘why’, then the prejudices embedded within land reproduced through language, have done their work. But if we do question our motivations, then the resistant elements that are also contained within, have done theirs. I am hopeful that the latter will continue to assert themselves in interesting ways and spaces, presenting openings even in situations where we suffer from an excess of control.